The Phoenix

Returns to

the Ashes.

What next for

Teesside airport?

Part 2

The will to control

Teesside International Airport terminal building

Scott Hunter

7 March 2023

(Reading time: 25 minutes)

A government in its death throes announces the creation of two new regeneration schemes, specifically the creation of development corporations for Middlesbrough and Hartlepool, and new powers have been bestowed upon the mayor to see them through. Significant assets currently managed by the respective councils will shortly come under the control of these corporations. A good moment to look closely at the Tees Valley mayor’s recipe for success in what has been his signature dish – the regeneration of Teesside Airport.

Or not, as the case may be.

An airport regeneration programme set up by Houchen in such a way that public money is made to disappear right in front of the eyes of the electorate as the aviation business founders, and a government which, it appears, is happy to allow him to spend without ever asking to see the receipts. Houchen, all the while, implausibly claiming the venture to be a runaway success. The devolution of irresponsibility.

In the first part of this series, we looked at the mismatch between the mayor’s recent pronouncements on the progress of the airport’s business and reality. But the problem is not of recent origin. In this part we examine how problems were created at the time the airport was brought into public ownership, and how, in the process, Houchen created a trap for himself.

Politically, the venture has brought the mayor tremendous popularity. That the regeneration programme for the airport has been aspirational for people in the Tees Valley, should not be underestimated. However, scratch beneath the surface of the TVCA business plan for the airport and it emerges as not just unrealistic, but obviously unrealistic.

His popularity also extends to Westminster, where a government devoid of practical ideas on how to solve the problems it created for itself over Brexit welcomed him as a person with vision, a man with a plan. A pragmatist among the ideologues. But successive prime ministers have failed to spot the fact that a can-do attitude and actual competence in real-world situations are not the same thing.

So, we consider the reasons behind the TVCA’s purchase of the airport from its previous owners, Peel Group, and the setting up of a new joint venture with Stobart Aviation to realise a ten-year turnaround plan. We conclude that the former was commercially irrational, and the latter was, to all intents and purposes, faked.

TVCA buys the airport from its previous owners

Presumably, Houchen was as surprised as everyone else when he won election as Tees Valley Mayor in 2017. Given that it seemed that it was the pledge to bring the airport into public ownership that swung it for him, he set about implementing that. The business plan for the airport was published in early 2019, but Houchen had already made it clear in statements to the press that that he unequivocally rejected the option of working with its then owners, Peel Group.

The background to this is that Peel Group had owned a controlling share in the airport since 2004, with the remaining shares being owned by a number of local councils. Its most successful year of operation was 2006 when it handled 900,000 passengers but it went in to decline after that, and by 2017 was handling only 131,000.

In that year, a debate was held in parliament where it was proposed by former Sedgefield Labour MP, Phil Wilson, that the government step in to support Peel, which at that time was losing £2 – 3 million a year on the airport, having previously invested £38 million in the business. Peel had itself produced a masterplan for the airport in 2014. Central government support was not forthcoming.

The 2014 plan, which recognised that the airport could not become commercially viable on the basis of aviation revenues alone, involved selling off a parcel of land for housing in order to raise funds to redevelop the remainder of the airport estate, in particular, the area known as ‘Southside’, where it proposed to create a business park. Aviation was expected to increase to around 200,000 passengers a year by 2020 but the future commercial viability of the business as a whole would be dependent to a significant extent on revenues from the business park.

With advent of the Tees Valley Combined Authority, it became feasible for the airport to benefit from public funds while continuing to be operated by Peel. And, indeed, the TVCA’s own business plan for the airport acknowledged the financial constraints Peel had been operating under:

“… it is not feasible for a private concern to carry the financial cost of enabling a wider economic benefit. In this instance the airport may be considered that rare thing in economics a genuine public good in terms of its wider economic impact …”

That ‘wider economic impact’, generally referred to as ‘catalytic impact’, is the spin-off benefit of an airport, by which it helps to stimulate the regional economy to a greater extent than just the number of direct and indirect jobs it sustains.

As for being a ‘genuine public good’ we might reasonable interpret that as being not necessarily returning a profit but something from which the public gains some value. It is therefore identified as a ‘strategic asset’.

But Houchen had an alternative plan, which was to buy out Peel’s share of the business. This was at a cost of £40m with a further £34.6m set aside to cover future losses and capital expenditure – a total of £74.6m. A ten-year turnaround plan was prepared that was intended to see the airport return to profit by 2026/7. Two companies were then set up – the trading company, Teesside International airport Ltd (TIAL), and a holding company, Goosepool 2019.

But why reject the pragmatism of cooperating with Peel for a high-risk and high-cost alternative? The simple answer to that question is that Houchen’s motivation was always more political than commercial.

Houchen’s politics, and the demonisation of Peel Group

Of those who have commented on Houchen’s politics, few have misunderstood his mentality quite as well as Will Hutton of the Observer, who, in 2021, wrote

“This do-it-if-it-works local Tory politician is reinventing the Conservative party as it attempts to deliver on its promise to level up. The string of initiatives Houchen has launched encompasses the ideological spectrum.”

In reality, Houchen’s career begins in earnest at the height of Brexit fever, in the age of ‘enemies of the people’, and it is the fingers-crossed economics of Brexit that properly defines his politics. The acquisition of the airport is a case in point. A hopelessly over-optimistic business plan was published that obscured the real commercial difficulties the airport was facing. Its publication also served to obscure the fact that a honey pot was being created in the process from which a select few were set to benefit.

That rhetoric is interesting in its own right as it involves not just rejecting the idea of cooperation with Peel but demonising them in the process as well. As the airport’s fortunes continued to decline after 2014, Peel determined that it should close in 2021, a decision that was agreed with the group of local councils who held a minority share. It was this decision that Houchen used in public against Peel.

The slogan that Peel and Labour conspired to run the airport into the ground is one that Houchen has repeated over and over again in the past five years, and continues to do so. A strange fate for a company whose main involvement in politics, in reality, is as donors to the Conservative Party.

In the event the company does not appear to have taken umbrage at the way it was being portrayed. As the Gazette reported in December 2018, the chair of Peel Group, Robert Hough, was quite ready to hand over the keys with a word of advice to the mayor that the new owners would need deep pockets and a ‘willing long-term investor’ to turn the business around. Peel then pocketed the amount they had invested in the airport during their tenure, and left Houchen to it.

When the TVCA business plan was published in early 2019, it had three constituent parts – the business plan itself and two independent consultants’ reports. One of these was aviation consultants, ICF (the second, by JK Property Consultants, we will examine in a later part in this series). There are significant differences between the TVCA/ICF plans, on the one hand, and the Peel masterplan, on the other. Consideration of these differences provides some insight into Houchen’s real intentions for the airport.

In commissioning the ICF report, the TVCA clearly presented a different brief to that given to the writers of the Peel report. Where Peel had considered how to make the airport as a whole commercially viable, ICF were tasked with examining ways to maximise aviation only. It did not deal with the development potential of the site as a whole:

“Property related revenues currently account for 50% of revenue. An increase has not been forecast as we understand the Combined Authority is consider property opportunities separately, but DTVA’s [Durham Tees Valley Airport, now Teesside International Airport] over all profitability is sensitive to its property performance” [sic] (business plan p84)

It is significant that, long before the TVCA’s business plan was written, redeveloping the rest of the airport site was already recognised as vital, but no published document exists that details how the TVCA intended to realise this. We might surmise from this that one of the underlying reasons why Houchen did not want Peel to continue to have a role in the airport was that they had not only recognised how important a business park was but had produced detailed plans for its creation. Would they have agreed to continue to operate the airport without also having a stake in the business park as well?

In the event, TVCA entered a joint venture partnership with Stobart Aviation to run the aviation side of the business, which commenced in March 2019. Almost twelve months later, the creation of the business park was finally announced, and it was to be a joint venture not with Stobart’s but with local property developers, Martin Corney and Chris Musgrave.

The ICF report aims to achieve the unachievable

The ICF report presents figures for the growth potential of aviation some of which are hugely in excess of those predicted by Peel, as shown in the table below, where aviation growth has three possible trajectories:

In this table, ‘organic’ refers to service levels remaining as they were in 2017 –18. Passenger numbers in this scenario increase from 131,000 in 2017 to 164,000 by 2027, so lower growth than had been predicted by Peel in 2014. ‘Seasonal/regional’ refers to an increase in holiday charters as well as increased scheduled domestic flights. In this scenario, passenger numbers are expected to grow to 372,000 by 2027. The third scenario, LCC, is where a low-cost carrier sets up a base at the airport and operates services from there. In this scenario, passenger numbers reach just under 1.6 million by 2027.

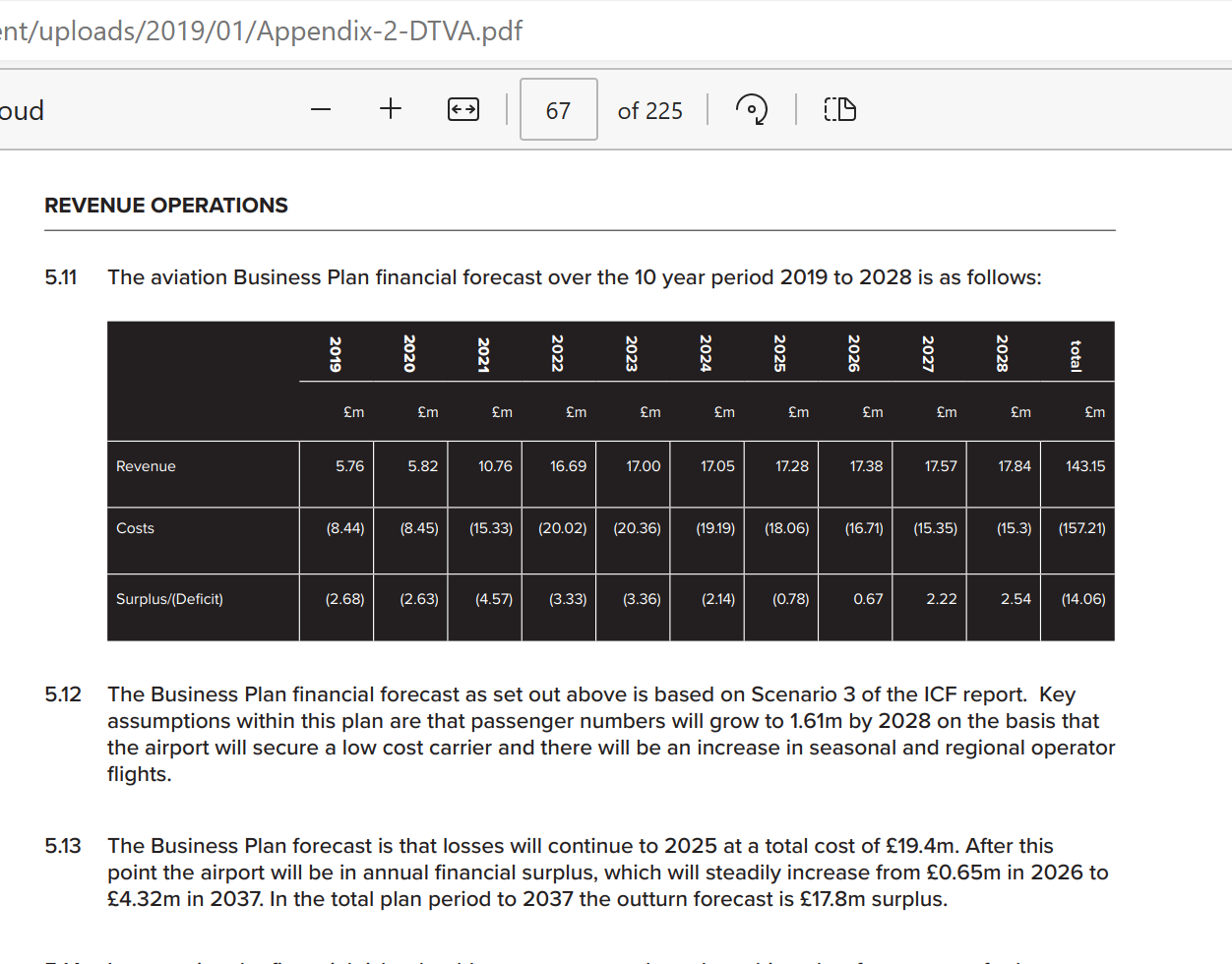

Given that the stated aim of the TVCA business plan is to turn the airport into a commercially viable business, it takes these projected passenger numbers and calculates how they translate into airport revenue:

As for scenarios 1 and 2, it predicts that losses will decrease between 2019 and 228, but profitability will not (quite) be achieved. However, there is a problem with these projections, which is that the basis on which they have been calculated is not presented.

Running counter to this projected revenue is a report in The Financial Times, in 2017, which observes that airports with fewer than 2 million passengers a year lose money. This has now become a benchmark. Even the most optimistic ICF forecast is well short of that critical mass. So how these revenue figures were obtained is a mystery.

But there is a further problem with the forecasts. Even if the forecast revenue is accurate, it depends on attracting a low-cost carrier to set up a base at the airport. ICF considers that Ryanair is the only carrier in a position to move out of its current bases at Newcastle and Leeds Bradford, but “is unlikely to [relocate] to an airport between two key markets where it is succeeding.” (business plan p112).

It is important that the carrier set up a base, rather than, as Ryanair does at the moment, simply using Teesside as a destination airport from its bases elsewhere in Europe. Setting up a base significantly increases the airport’s revenues. But that is not the only issue. There is also the matter of projected passenger numbers.

Take 2022, for example. Subtract the passenger numbers in scenario 2 from those in scenario 3. This gives you the number of passengers expected to be using the LCC flights, which is just over one million. To carry that number of passengers there would need to be around 15 flights a day, 365 days a year, all of them full to capacity (189 passengers in the case of Ryanair planes).

And how does ICF arrive at this extraordinary level of increased demand? There are two components: one is spillage, the other is increasing the ‘propensity to fly’ of people in the area. ‘Spillage’ is the number of passengers from the Northeast who use airports outside the region who need to be attracted back to Teesside. ICF states that this is around 5.5 million per annum (CAA figures). ‘Propensity to fly’ is the number of flights taken per person per year in the region. The Northeast has the lowest propensity to fly of any region in the UK, a fact that the report admits is a function of low per capita income. One of the ways in which passengers numbers were to increase was to increase the ‘propensity to fly’ of people living in the region. In other words, persuade people on low incomes to spend more money on foreign holidays.

At this point, ICF delivers contradictory messages. Having said that it is unlikely that any low-cost carrier will set up base at Teesside, it suggests that it may, after all, be possible provided the airport has what it calls ‘driven management’. But ‘driven management’ is itself problematic.

In search of ‘driven management’

Long before the business plan was written, Houchen had made it abundantly clear that he didn’t want Peel Group to continue as airport operator. However, the staff were to be retained by the company – TIAL – being set up to run the airport. The problem was that, while the management team on site handled the day-to-day running of the business, the executive and strategic management was carried out at Peel’s headquarters in Liverpool, and the airport, now more than ever, needed people with their expertise, as can be seen from the ‘Arrangements for benefits realisation’ table in the business plan:

In short, the airport operator alone was tasked, of necessity, with achieving all of the wildly optimistic outcomes of the ICF forecast. Surely any competent operator would look at the projections, reject them as hopelessly unrealistic, and walk away from any deal. Houchen, it seemed, had shot himself in the foot by repudiating Peel, as a vital layer of management was lost in the process, and a replacement was going to be hard to find.

But Houchen did find an operator – Stobart Aviation – that was willing to take on the job (and it was, in fact, Houchen who found the partner, not TVCA CEO, Julie Gilhespie). That left only the matter of agreeing the terms.

Houchen brings in Stobart Aviation as joint venture partner

The introduction to the business plan makes clear, although without directly referring to the joint venture partnership, that the mayor has the necessary powers to carry out the plan:

“33. The Combined Authority has powers pursuant to section 113A of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 to do anything it considers appropriate for the purposes of carrying out its functions …”

With regard to the joint venture, it states,

“30 … a Joint Venture Agreement shall be entered into which will govern the relationship between the Combined Authority and the preferred operator [Stobart Aviation].”

The terms specified are to do with voting rights and the sharing of profits/losses. It also specifies that Stobart would provide an airport operator, which was one of its subsidiaries – London Southend Airport Ltd.

As to quality, it has this to say about Stobart Aviation:

“25. The preferred operator has successfully grown another UK airport significantly in recent years. This experience in particular makes the preferred operator an attractive organisation to provide strategic direction and oversight ... The preferred operator’s contacts with target airlines would also be helpful.

“26. The preferred operator is keen to extend its role in regional aviation and sees this as a sector with a growth opportunity, particularly through the application of new forms of customer marketing and relationships with airlines.”

And so legal formalities were concluded and put in place “a Joint Venture Agreement with the preferred operator pursuant to which the preferred operator would take a share of no more than 25% of the Combined Authority’s equity interest in the airport as an incentive mechanism to reduce ongoing losses ... This arrangement would be subject to the preferred operator funding its share of the losses in the interim…”

In other words, the TVCA settled the full cost of buying the airport, and then gave Stobart’s 25% of the shareholding, in what appears to be an act of extraordinary generosity. Until you consider, that is, that no one would have put money into a scheme whose business plan was so unrealistic. Houchen had found a partner but not an investor.

Although there is no further detail in the plan, it seems that Houchen’s generosity did not end there. What it does not tell us is the nature of the agreement with respect to the responsibilities of either partner should one seek to dissolve the partnership, as Stobart did in the summer of 2021. We shall return to this point shortly. But first it is necessary to clarify what Stobart did and did not do while the partnership was in existence.

Stobart starts to implement the turnaround plan

Stobart’s success during the time it was involved with Teesside is unmistakable – first Eastern Airways and later Loganair offered domestic flights to a number of destinations. TUI returned with summer charters, Ryanair entered a five-year contract to fly to Teesside, flights to Heathrow resumed, and KLM entered a 7-year contract with the airport. All of this, moreover, at a time when Covid had plunged the aviation industry into turmoil.

Oddly, however, while it was committed to the work of airport operator, it showed little interest in influencing the business in its capacity as shareholder. It appointed a representative, Kate Willard, its Director of Partnership Development, to the board of the holding company, Goosepool 2019. Her Linked in profile states, however, that she ceased to be employed by Stobart’s in December 2019, at which point they did not replace her on the Goosepool board. In fact, she continued to serve on that board until 2022, when she became chair of TIAL.

A further indication of Stobart’s lack of involvement in the airport venture as a whole is seen in stobart-group-limited-2020-annual-report where Teesside Airport is nowhere mentioned (not even in the section on p166 entitled “Associates and Joint Ventures”). Given their 25% shareholding in the business and their role in delivering a business turnaround, we might consider that it merited at least some comment.

In October 2019, the airport’s website announced that Stobart CEO, Glyn Jones, was to be interim managing director until a permanent MD could be appointed. However, his name does not appear on the Companies’ House list of directors for the airport, so it is unclear whether he really took on this role in anything other than name.

Stobart departs the joint venture

By mid-2020, Stobart Group’s business was experiencing some turbulence, and in June of the year Investors' Chronicle was reporting that the company was going to concentrate its efforts on its aviation division, particularly Southend Airport. Then in July 2021, it severed its relationship with Teesside. At the time, some critics accused Stobart of ‘jumping ship’ and ‘evading liabilities’, but that interpretation contradicts the position given by Investors’ Chronicle.

Given that Teesside Airport had a contract with the Southend Airport company, it would appear that its position was strengthened by the situation reported by Investors’ Chronicle, not weakened. So, did Stobart’s take a hard look at Teesside subsequently and decide it was a bad risk? And what would the consequences of abandoning the joint venture agreement be?

The business plan clearly states that legal arrangements had been finalised with the Stobart’s, and that it would be liable for a share of the airport’s losses (Decision, para 1(ii)). Is it reasonable to expect that, should one party terminate a contract (and the plan states that the operating contract was to run for ten years), there would be a penalty. After all, Stobart’s were leaving the airport in the lurch by walking off the job.

In fact, there is no evidence that this is what happened, which leads us to question what the terms of that Joint Venture Agreement might have been. Filings for the airport company for 2021 show that far from there being a penalty, the airport operator received £1.5m, up from £646,732 the year before:

Source: Companies House

And Stobart Group’s annual report for 2022 (now renamed Esken) repeatedly mentions receiving a one-off payment from Teesside Airport when their relationship was terminated (referring to “£3.5m of one-off receipts in connection with Connect Airways and Teesside International Airport.”). So, far from being penalised for terminating the joint venture agreement, Stobart’s appear to have been compensated.

Furthermore, in a published letter, Esken (Stobart) give the impression that, far from ‘jumping ship’ they had, in fact, become surplus to the airport’s requirements, as if they were splitting up by mutual consent:

"Over the last 12 months, Teesside International Airport has secured an airline partnership with Loganair, attracted new routes and installed a strong, experienced leadership team, with the oversight of the Tees Valley Mayor and Combined Authority. Given these positive developments, Teesside International Airport no longer requires the support of Esken as an external strategic partner.”

The letter goes on to state that, should the airport close before January 2023, Esken (Stobart) would be entitled to compensation of up to £31.3 million! So, by this point, the stipulation in the business plan documents that “This arrangement would be subject to the preferred operator funding its share of the losses in the interim” has vanished.

Passenger numbers in 2022 were around 160,000, so a little over one tenth of ICF’s scenario 3 target. Aviation growth came to an abrupt halt when Esken (Stobart) left and has since declined rapidly; by the beginning of April 2023, Loganair will operate only one route from Teesside. Ryanair will be increasing holiday flights from 7 to 14 per week but will offer no new destinations (in contrast to their expansion at other UK airports) and all flights will cease at the end of October. The connection to Heathrow ceased in May 2022. All of which indicates that, in actual fact, Teesside needs Esken (Stobart) more than ever.

Furthermore, in the light of what we now know about the terms of the joint venture agreement, Stobart’s involvement was clearly low risk. So why pull out?

Two things about Stobart’s statement are remarkable. One is the mention of Loganair. Why single it out? After all, Eastern, TUI, and Ryanair had all returned to Teesside. Perhaps it is because there is something contentious about the deal with Loganair. Early in 2020, Eastern had announced it was returning to Teesside, offering a range of UK destinations. In November of that year, Loganair then announced it would be offering flights to the same destinations, in direct competition with Eastern. Was there sufficient demand for flights to allow both carriers to operate? Not, as it turns out, and Eastern shortly withdrew most of its services and left Loganair to it.

Was the partnership with Loganair more favourable than the one with Eastern? That does not appear to be the case. The website ch-aviation states that Eastern was offering flights to seven destinations and would be basing three aircraft at Teesside. It observes that Loganair offered five destinations, basing one aircraft at the airport. This would indicate that the relationship with Eastern was the more lucrative. So who negotiated the Loganair deal?

We cannot directly answer that question, but we reported (airline-competition-at-teesside-airport) at the time that Houchen made a video with the chief executive of Loganair, Jonathan Hinkle, promoting the new services, as well as placing advertisements on local radio, observing that it was surprising that he should do so given that a competitor airline was also based at Teesside.

All of which leads to a question. Did Stobart’s consider that they had become surplus to Teesside’s requirements because of the mayor’s interference in the marketing of the airport’s services? And which brings us to our second point about the Stobart/Esken statement which is the mention of “the oversight of the Tees Valley Mayor”.

The mayor interferes in the running of the airport

The whole point of setting up the airport as a private limited company was that it could function as a commercial organisation without external interference. It should have been the holding company – Goosepool 2019 – that took on the role of scrutinising the work of the airport company and reporting back to the TVCA. This is not what was happening. Houchen was taking a very direct interest in the airport. His involvement with the Loganair partnership was the most egregious, but not unique. And his interference in its operations, at times, verged on the ridiculous.

“26. The preferred operator is keen to extend its role in regional aviation and sees this as a sector with a growth opportunity, particularly through the application of new forms of customer marketing and relationships with airlines.”

In the event, that new form of customer marketing turned out to revolve around Houchen himself to the exclusion of all else. No sooner had the purchase gone through than Houchen became the poster boy. The airport has provided him with a never-ending source of propaganda, but, as with the cargo flights, the reality has never quite matched the rhetoric. Moreover, the subtext of all of the promotion is ‘how good am I?’ It was self-promotion, not airport marketing.

As for ridiculous, in late 2020 Houchen claimed that, when TUI announced it was resuming flights from Teesside, this was the low-cost operator (LCC) the business plan foretold, only to claim a month later, when Ryanair pledged to use it as a destination airport, that this was, in fact, the dreamed of LCC:

Stobart, with its ‘new forms of customer marketing’ had been side-lined. And possibly its ‘relationships with airlines’ as well.

Read the explainer about types of carriers (with apologies in advance to those who think they’re now being patronised):

Had the nonsense about attracting a low-cost carrier been confined to propaganda by Houchen himself, this would have been vexing enough for Stobart’s; but in reality it went further than that. It is repeated in the filings for Goosepool 2019, where in successive years we find statements like the one below from the 2022 statement of accounts:

“The directors have prepared long term cash flow forecasts for TIA. These forecasts include the airport securing a number of low cost carrier airlines and are based on known secured contracts of those which are currently being negotiated. The securing of these contracts is in line with, and in some cases, ahead of the long term business plan set out when TIA was acquired.”

It seems that the directors of Goosepool 2019, having drunk the Kool-Aid, are repeating the same line in official documents, as if the need to be seen by Houchen to be toeing the party line matters more than revealing to the rest of the world that they don’t know what they’re talking about.

There remains one final issue to be considered which is, given Stobart’s apparent lack of engagement in strategic management of the venture, did Houchen gain anything from the partnership? The answer to which is that he most certainly did because the fact that there was a joint venture meant that the TVCA did not own 100% of the shares, which, in turn, meant that neither TIAL nor Goosepool 2019 were subject to freedom of information legislation. Freedom of Information applies only to bodies that are 100% in public ownership, so the partnership delivered Houchen one of the things that has become the hallmark of his office - the veil of secrecy. (There remained the TVCA scrutiny committee but that he contained by either failing to turn up to meetings or by refusing to disclose key information on the grounds of commercial sensitivity, given that TIAL was a private company).

So, essentially, Houchen faked the joint venture with Stobart’s. In reality they contributed only as airport operator, and even then, Houchen interfered, making the job yet more difficult than it needed to be. And, given the fact that the targets set for aviation development were wholly unrealistic, they already had a mountain to climb. Peel had to be ousted not because they were ‘less motivated’ but because they would never have agreed to submit to the wholly unrealistic aims of the venture and allowed themselves to become subservient to Houchen’s political ambitions. But if his dismissal of Peel made a bad situation worse, the departure of Stobart’s made things worse still.

Stobart’s statement contains one significant error, when it says that the airport had “installed a strong, experienced leadership team”. It hadn’t, and moreover, Houchen was already preparing to have it embark on a massive spending spree. The leadership team, the significance of the spending spree, and how the mayor dealt with the problem of being handed back Stobart’s shares will be the subject of the next episode in this series.

We conclude this episode, however with a comment by Houchen’s alter-ego on social media, responding to criticism that the mayor always claims credit personally for purported achievements at the airport, never giving credit to the work of his ‘team’:

So, it looks as if his alter-ego has the measure of him ...