Mass Mortality

in Tees Bay.

Defra on the

Defensive over

Toxic Dumping

in North East

Waters

photos taken at South Gare and Skinningrove on 31 May, the day the Defra report was published

Scott Hunter

15 June 2022

Defra published its latest report on mass crustacean die-off in Tees Bay on 31 May. It is a curious and self-serving document that raises more questions than it answers. Some of those questions bear, not simply on the causes of that catastrophe, but on Defra’s integrity as guardian of the environment.

The report insists that the conclusion Defra and its partner agencies reached earlier this year - that it was the result of naturally occurring harmful algal bloom – remains the most likely, and all other possible explanations are manifestly false. While glossing over just how superficial the investigation was, it also sidesteps the issue of subsequent die-off, which now includes fish and seaweed.

The conclusion that the first wave of die-off was as a result of algal bloom is tenuous at best, as we discussed in an earlier article (Pollution in the Tees Estuary. Are Things about to get Worse?) And in any case, unless we are to believe that algal bloom has now taken up permanent residence in these coastal waters, it does not offer us any explanation of the subsequent die-off.

We have previously sought to demonstrate that the Defra investigation was not thorough. Here we ask the question why: why did Defra and its partner agencies content themselves with such a poor investigation into the causes of the crustacean die-off? Our examination of marine licence and related documents has revealed a possible explanation for this, but a disturbing one.

Essentially, the evidence we have uncovered is that while Defra and its partner agencies have a set of standards for the protection of coastal waters against contamination, these are set aside when dealing with the Tees and the Tyne. The Marine Management Organisation (MMO) issues licences to dredge these two rivers even when they have obtained sediment samples that show elevated levels of contamination.

Defra Dismisses Chemical Contamination as a Possible Cause of the Die-off

The report’s authors state that the die-off was not the result of a single catastrophic discharge event (such as the fire which occurred at an industrial plant in North Tees in September). It also discounts the possibility of it being sewage outfall. The other possible source of chemical contamination would be disturbed sediment. The report has this to say about the tests it carried out:

“The Environment Agency analysed water, surface sediment and blue mussel and crab tissue, considering over 1,000 different chemicals (The Environment Agency’s scheduled contaminant sample data can be found in the Water Quality Archive on data.gov.uk as part of the public archive). As well as processing samples using their standard, fully established laboratory methods, the Environment Agency’s laboratory service modified their water screening methods to look for unusual traces of contamination in the sediments and crab flesh.”

Initially, and, as it turns out, naively, we thought this meant that Defra had published the data (at least that on water and surface sediment). So, we checked this document, only to find that it does not contain this sampling data at all. The closest is gets is data of unplanned monitoring on the coast off the Tees in mid-November. Defra reports, however, that sampling of water and sediment was undertaken in early October. So, Defra uses this routinely gathered data to create an impression of transparency, an impression that turns out to be a mirage upon closer examination.

It then concludes that

“… no chemicals tested were identified at levels which would consistently explain the cause of the mortality event over the spatial and temporal scale observed.”

Which Chemicals? Where Might They Have Come from?

The chemicals in question here, were what the report refers to as ‘organic pollutants such as pesticides’, dissolved metals, and cyanide. We know from earlier reports (SLAB5_Report_2011-12) by Cefas (Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture, one of Defra’s partner agencies), that sediment dredged from the Tees and deposited at one of the disposal sites is consistently high in a group of contaminants known as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (or, PAHs). There are two drop zones for dredged material off the coast of the Tees. Tees Outer is used only occasionally; the one in constant use for maintenance dredging is known as Tees Inner (or, Tees Bay A).

On 26 November 2021 Defra issued a press release on the die-off. It stated:

- “Undersea cabling, seismic survey activity or dredging have also been ruled out as possible causes”

Some months before the diagnosis of harmful algal bloom (HAB) was made, therefore, dredging had already been eliminated. Many people were unconvinced by this, and local inshore fishermen in particular were asserting that dredging was the most likely cause. While this opinion was reported in the local press, no one asked them what evidence they had to support this claim. Until we did.

The Case against Dredging

And when we did, we got in response, what government agencies these days often seem incapable of – a straight answer and some data to back it up. We present their case here. Before doing so, however, we should point out that there are those who now simply assert that dredging must be the root cause of the die-off, while others take a more nuanced view and insist that if Defra has credible evidence that dredging is not the cause, then it should present evidence to support this conclusion. This is something Defra has thus far singularly failed to do.

Here’s the background. The harbour authority, PD Teesport, has a statutory duty to maintain the shipping channel in the Tees at a specified depth. It therefore undertakes regular maintenance dredging using two local dredgers – Cleveland County and Heortnesse. It has been reported to us that, during the late summer of 2021, both were in dry dock awaiting repair. The harbour authority therefore brought in another, much larger, vessel – the UKD Orca.

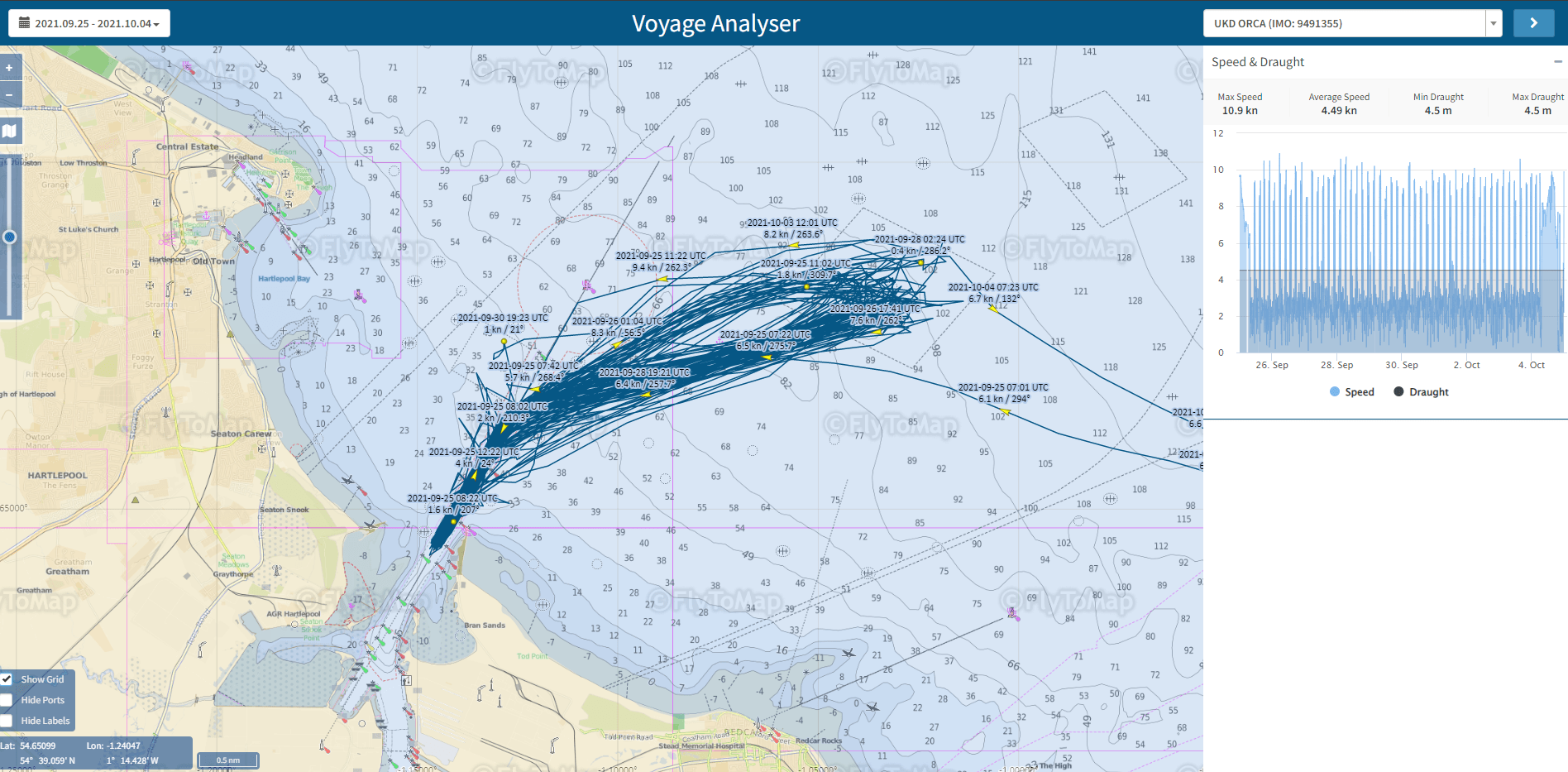

Below is the tracking data of the Orca’s movements while it was in the Tees Bay area:

Now if that appears to you to be just a load of scribble, we can reassure you that this was exactly our initial reaction as well. So, we went back and asked for an explanation. It turns out that the image shows that the Orca made approximately 52 trips to the drop zone (which is known as Tees Inner, or Tees Bay A, about 7km off the coast) between 25 September and 4 October 2021 – a ten-day period. The Orca’s capacity is known, and so the volume of material it removed from the channel can be calculated. That calculation indicates that it removed 123,396m3 of material. This now needs to be put into context.

The MMO (Marine Management Organisation, one of Defra’s partner organisations) issues PD Teesport with a ten-year licence to undertake maintenance dredging in the Tees. That licence permits them to dispose of a total of 187,570m3 of sand, sediment and silt from the Tees annually. The Orca dredge therefore, moved 66% of that annual quota in the space of ten days. That’s a significant intensification of dredging activity. So what?

As we have explained in a previous article (troubled-waters-the-forces-behind-the-death-of-the-tees), dredging poses a risk to the marine environment in various ways. That such risk exists is not in dispute. In applications for marine licences for capital dredging projects the environmental impact assessments that accompany them are very explicit about it. When dredging takes place a plume of dredged material is released both when it is picked up and again when it is released at the drop zone. This results in oxygen depletion in the water, wherein lies a risk to marine life.

That risk applies even when the dredge material is clean, which is not the case in the Tees. The report goes on

“Cefas completed an indicative 2D tracking model of the potential sediment plume from the dredge disposal site. The model indicates that the plume extents are relatively confined along the tidal excursion at the disposal site and do not have the same geographic extent that would be consistent with the reported scale of mortalities.”

Now, their modelling may accurately describe the extents of the plumes as the sediment is discharged, but does not show the movement of the toxins released during this operation. It is another sleight-of-hand by Defra. Because dredge plumes are themselves a danger to aquatic life, they omit mention of the additional dangers when those plumes contain contaminated material.

Who Collects the Sampling Data on Sediment?

Analysis of sediment is the responsibility of Cefas (the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture, another partner agency of Defra). The collection of samples for analysis is the responsibility of the harbour authority, is carried out every three years, at which point the dredging licence is reviewed.

Consultants Royal Haskoning, in their environmental impact assessments for the Northern Gateway Container Terminal and the South Bank Quay (MLA/2020/00507 and MLA/2018/00079), state that dredged material in the Tees is principally sand that arrives from further out in Tees Bay. This, combined with the evidence presented in SLAB5 indicates that contaminants already in the estuary bed mix readily with the deposited sand, even though it remains in the channel for a relatively short period of time before being removed by maintenance dredging.

It is important to note that, while Royal Haskoning claims, in its environmental impact assessments for projects in the Tees, that maintenance dredging is removing ‘clean sand’, this is not , in fact, the case. All of the material removed is contaminated to some degree, principally with PAHs. What appears to happen in normal circumstances, however, is that this is not in sufficient concentration to cause extensive damage to the marine environment in and around Tees Bay.

By massively increasing the intensity of dredging in late September 2021, the Orca appears to have taken a much larger quantity of contaminated material to the drop zone than would otherwise have been the case. Which is why it is surprising that Defra appears to dismiss the issue of dredging without giving a full explanation of its reasons for doing so. The May 2022 report states the following:

“A range of possible sources of contamination were considered such as industrial and wastewater discharges, as well as sediment disturbance activities (dredging). Environment Agency regulatory officers checked for any unusual activity in industry or water companies that discharge into the Tees Estuary and immediate coastal area. No abnormal site activities or non-conformances with numeric permit conditions at any of the sites were noted.”

Notice that the check for unusual activity relates to industry and water companies, not to dredging. For dredging, it appears that licences were checked, which means that, if, as we assume is the case, that the harbour authority did not exceed its annual quota for dredging, its activity was not classed as in any way unusual. The fact that abnormally intensive dredging had taken place is nowhere mentioned in the report.

While the report discusses the possibility that one particular PAH – pyridine – may have been the cause, little attempt is made to connect that directly to dredging, despite the fact that contaminated sediment is the most likely source:

“The Environment Agency’s analysis focused on organic pollutants, including pesticides, based on the behaviour of the dying crabs and the targeted nature of the impact. However, Cefas also conducted metal analysis (including for chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic, cadmium, lead, selenium, manganese, iron and mercury) of the soft tissues from crabs.”

Another statement that fails to convince. Two sentences, the longer one unnecessarily naming some of the metals it tested for, the shorter one omitting to name any of the hydrocarbons that are known to be contained in sediments in the Tees. Defra skimming over details once again.

This is not the first time that Defra and its partners have shown themselves to be shy about discussing PAH contamination in the Tees. In his report on the original die-off, independent consultant, Tim Deere-Jones observes that the SLAB5 dredging monitoring report of 2014 omits analysis of hydrocarbon contamination at the Tees disposal sites, while including it in discussion of other sites around the coast. This was in contrast to its 2012 report, that considers the matter in some detail. SLAB5 monitoring was conducted out by Cefas in conjunction with the MMO (Marine Management Organisation).

We ourselves were puzzled by some of what was contained in the Royal Haskoning Environmental Impact Assessment for the Northern Gateway Container Terminal. Its sediment sampling revealed that of the 22 PAHs tested for, the concentrations of 19 of them exceeded Defra’s threshold for safe disposal at sea. The report recommended disposal at sea nonetheless, and this was accepted. The MMO issued the licence allowing all of the dredge material to be disposed of at the Tees Bay C drop zone. This contradicts the following statement from the May 2022 Defra Report:

“Samples of dredge material must meet the highest international standards protecting marine life before it is permitted to be disposed of at sea. If samples analysed for contaminants do not meet the standards, the disposal to sea of that material will not be licensed.”

So has the MMO really set aside its own regulations to allow toxic dumping at sea? It appears so. But why? Isn’t the protection of the marine environment part of the job? It turns out, that it is in some places but not in others.

While investigating the work of the UKD Orca, we checked the maintenance dredging licence issued to the harbour authority, PD Tees, and some of its updates. A licence such as this is issued for a ten-year period, and one of its conditions is that the harbour authority provide sediment samples for testing every three years (that being the ‘highest international standard’ referred to above).

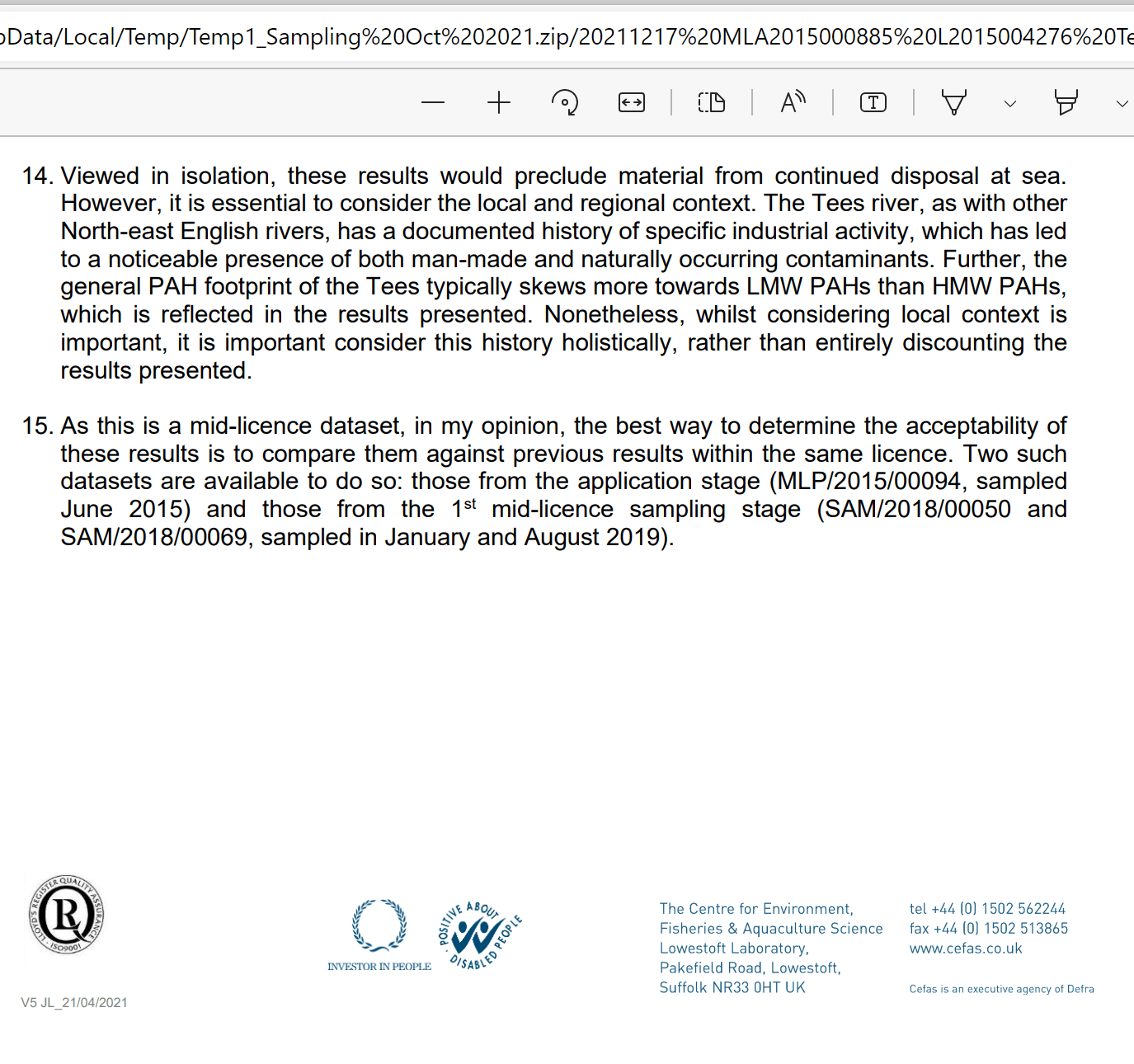

Our attention was drawn to paragraphs 14, 17 and 18 of that document. Having presented sampling data showing elevated levels of PAHs, it states,

In other words, the MMO is quite prepared to set aside its own standards when dealing with issues in the Tees. Cynics might begin to question whether this might lie behind Cefas’ reluctance to present the data it gathered, at which point the whole concocted explanation begins to look increasingly shaky. So, we wrote to Defra, presented them with the screenshots shown above, and asked them for comment. To be honest, we wrote in the expectation that we would be cold shouldered and never hear back from them. But no. They replied saying that they were dealing with our inquiry and asked us to be patient. So, we waited. And waited. After several days their response arrived.

It turns out that, contrary to what is claimed in the May 2022 report, Defra applies what it calls ‘regional contextualisation’, which is essentially what is described in paragraph 14 of the Cefas letter in the screenshot above. In so doing it claims to work in accordance with international standards, known as OSPAR.

We thanked them for the information and said we would include it in this article, whereupon they wrote back and said the statement was for reference only and we should not quote them on it. They did not seek to explain why they had made a contradictory statement in the May 2022 report.

As Defra prefers that we do not publish their own words in explanation of this, we shall provide an explanation in our own words:

The more pollution that there is in any marine environment, the less likely Defra is to apply its own regulations to managing it.

Which is cold comfort for people living in an area such as the Tees Valley. Many of our readers, on the other hand, may find themselves more in our agreement with our own view, which is this:

The industrial revolution is now over. It’s time to clean up the mess it left behind.

And for the benefit of those who would regale us with enthusiastic tales of the government’s levelling-up agenda, we might restate our view more simply as follows:

Levelling up involves cleaning up.

Correction

This article was amended on 4 September 2022 to show that 22 hydrocarbons were tested for, of which 19 exceeded Cefas levels for safe disposal at sea. It had earlier been incorrectly claimed that tests were from 33 out 36 hydrocarbons tested for. In fact the results come from the testing of 36 samples.