Poison Earth:

How Teesworks

Exports its

Toxic Legacy

Construction work at South Bank Quay, Teesworks

Scott Hunter

4 November 2022

No sooner had the Redcar Blast Furnace been extinguished than the region on the south bank of the Tees became a development corporation. A vast tract of wasteland with an industrial past and a promising future, or so we were led to believe. Then the cracks began to appear.

First was the hasty demolition of the Dorman Long Tower in September 2021. Early in 2022 there was financial scandal after the mayor quietly arranged for 90% of shares in Teesworks Ltd to pass to two local businessmen. Between these two events was another incident, apparently unrelated, which was the start of a massive and sustained die-off of crustaceans in Tees Bay from October 2021 onwards.

When the Defra-led investigation, in early 2022, discounted pollution as a likely cause, a campaign was launched to persuade them to reconsider, something which they steadfastly refused to do despite the mounting evidence that their investigation had been less than thorough. The evidence of both sides was eventually heard by the Environment Committee on 25 October, and its advice to the Secretary of State was published a week later. That evidence included an alternative explanation for the die-off that proposed the cause to be pyridine contamination in the water body and sediment of the bay.

The letter to the Secretary of State is, on the one hand, very encouraging, in that it recommends that the evidence of pollution as a cause of the die-off be taken much more seriously than has been the case until now, but on the other hand, there are some notable gaps in it. One of these is Teesworks, of which there is no mention.

Which is a questionable decision, given that it demands that the possibility that the die-off was caused by the contaminant pyridine be taken much more seriously by Defra than it has done until now, and the fact that if there’s one thing the Teesworks site has in abundance it’s pyridine. Although we should point out that other contaminants are available. Lots of them.

What is discussed at some length in the letter, quite understandably, is the possibly crucial role played by the dredging of the estuary in the die-off. Satellite imagery appears to show that whatever triggered the die-off, originated at Tees mouth where maintenance dredging had recently been taking place. It recommends that maintenance dredging of the shipping channel should continue but should be kept to a minimum while further investigation takes place. It recognises that, without maintenance dredging, the channel would soon have to close for shipping so it cannot be halted altogether.

What is surprising, however, is that a similar attitude is not adopted towards the capital dredging for the South Bank Quay project. That work, unlike maintenance dredging, is stoppable, but the letter does not explore that option. The letter proposes that there be a re-examination of acceptable dredging methods, and that the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) review dredging activity in the Tees. Yet it is known that the estuary contains large amounts of contaminated sediment that has lain undisturbed for years, now to be raised and most of it dumped at sea, with indeterminate consequences. Campaigners had asked for a temporary moratorium on capital dredging. The EFRA Committee does not seek to explain why it has rejected that demand.

Shutting the Stable Door after the Horse Has Bolted

The letter also recommends the establishment of an independent scientific panel to review both the pyridine and the (Defra-inspired) algal bloom theories for the die-off. This, again, is welcome. However, there it risks shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted, given the potential for the ongoing capital dredge at the South Bank Quay to mobilise a tidal wave of contaminated material into the bay. And for the benefit of anyone who thinks we might be overstating the case we offer the following evidence.

The South Bank Quay is a project in two phases, both of which will involve dredging different parts of the estuary. In phase one, 715,000m3 of sediment will be removed, all of it contaminated in varying degree. Of this amount approximately 125,000m3 is prohibited from disposal at sea under the MMO licence. This material is contained in an area at the north end of the main dredge zone. It can be seen on this map around the sampling point marked as BH34:

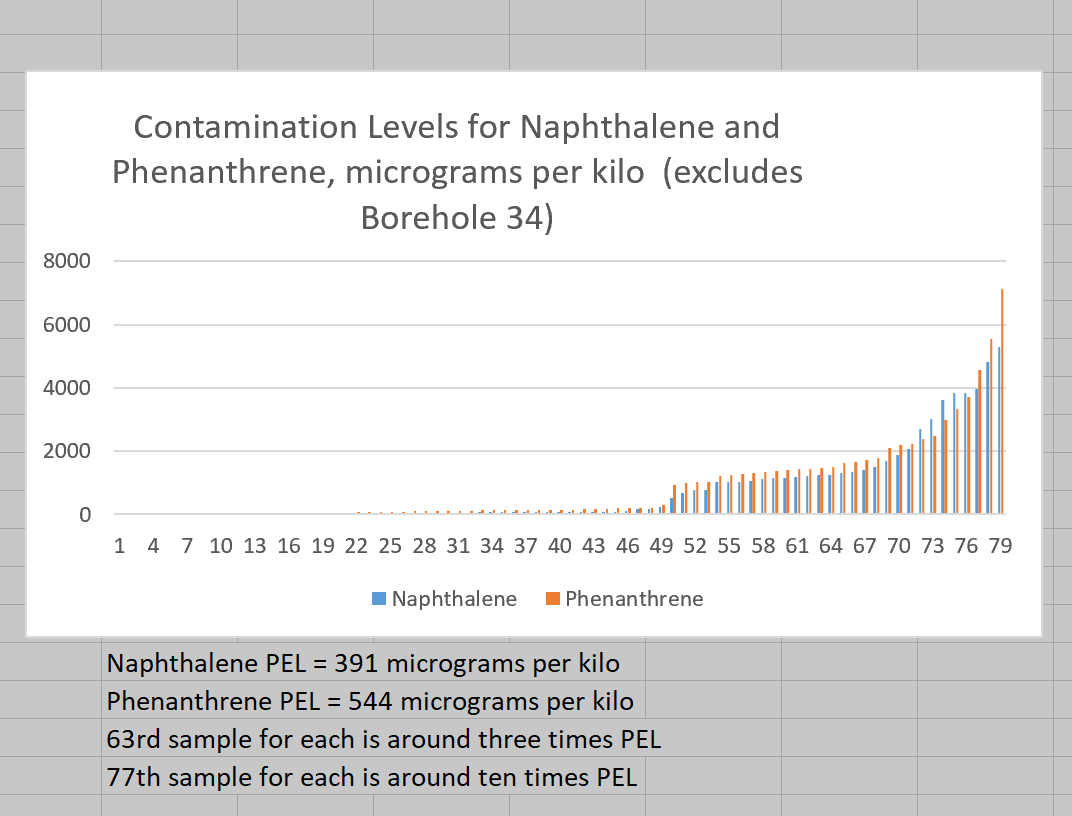

Just how much more toxic this area is than the rest can be seen from the following charts. These show the contamination levels of just two hydrocarbons, Naphthalene and Phenanthrene. The first chart shows, in rank order, the concentrations of these chemicals from all of the sampling locations excluding BH34. The second chart shows the concentrations, but this time includes BH34. Check the difference in the y-axis between the two charts. The difference in scale is enormous:

Source: Marine Licence Application MLA/2020/00506

So, we began by asking the simple question – why is the area around Borehole 34 so much worse than everywhere else?

And then we looked at a map of the area:

Source: South Tees Development Corporation Masterplan, 2019

In the centre of the map is Tees Dock. To the left of it are two watercourses – Lackenby Channel and Cleveland Channel. The thin dark blue lines show culverts – where the becks and channels have been covered over and now run underground. So, a culvert leads from the Lackenby Channel to the Estuary. Compare the location of the Main Lackenby Outfall with Borehole 34 in the earlier map, and it is evident that they are very close to each other.

At the other end of the main channels are more culverts – Kinkerdale Beck Culverts, Knitting Wife Culverts and Holme Beck Culverts. It is Holme Beck that, for the time being, is of particular interest.

A larger map of the site would show that it runs through the area now known as Dorman Point, previously Grangetown Prairie. Teesworks’ Dorman Point Environmental Statement (Chapter G Appendices) states that there remains a coke oven gas main (COGM) above ground on the site. This was, in fact, the site of the Cleveland Coke Ovens, long since demolished. But it has been reported to us that these ovens stood on top of Holme Beck Culvert.

Dorman Point Environmental Statement vol 2 Chapter G states that the Cleveland Channel, into which Home Beck discharges “ … is understood to be filled with highly contaminated water and sediments” (p36).

When the South Tees site was awarded upper tier COMAH status (control of major accident hazards) the specific nature of the hazard was the danger to the marine environment:

So, Holme Beck flows through an area of contaminated ground and discharges into the heavily contaminated Cleveland Channel, which in turn flows into Lackenby Channel which then discharges into the estuary in the vicinity of Borehole 34. And what precisely it discharges into the estuary is a matter of some concern.

It has been reported to us firstly that the water around the Lackenby Outfall ‘bubbles’, and also that, at certain times a film spreads out across the water. PD Ports clean this and do so at some periods in the year as frequently as once a week, by basically mopping it up. The discharge is at its most intense after periods of heavy rain. PD Ports has confirmed to us that they continue to carry out this maintenance work, even as the estuary is being dredged of contaminated sediment.

So, our recommendation to the Secretary of State for the Environment is not only to direct the MMO to “urgently review the dredging activity in the Tees”, but also to check why there continues to be contaminated material being discharged into the estuary at the same time as dredgers are working to remove layers of sediment.

Dorman Point is one of the areas of the site that is, supposedly, ready to be leased out, and therefore, by implication that any hazardous material has been appropriately dealt with.

It is therefore necessary also to consider whether adequate precautions have been taken to ensure that contamination on land is being neutralised (we believe that such neutralisation has not taken place at Dorman Point, but that the land has simply been overlaid with a mixture of shale from the Whitby Polyhalite mine and hardcore, but that, admittedly, is subject to verification).

By association, it is not sufficient for Defra’s agencies to focus attention solely on dredging. There is a heightened risk of contamination seeping into estuary waters and sediment when construction work takes place on the bank. The fact that PD Ports continues to have to clean up he area around the Lackenby Channel may be evidence of indifference to seepage of contaminants by Teesworks.

But let’s be clear, the discharge of contaminants from the Lackenby Outfall is unlikely to have been the cause of the 2021 die-off. It provided a more or less continuous discharge of toxic material, not a sudden surge. What it offers, however, is an insight into just how serious that contamination can be even without the added impetus of construction work on the site.

The consultants, JBA Ltd, who prepared the Environmental Statement for Teesworks, drew on information from a range of published sources. Prominent among these was the Environment Agency. And what we have presented here is quite familiar to that agency. Yet the Environment Agency appears to be let off the hook in the Environment Committee’s recommendations, as it was let off the hook on the day of the hearing. It has to be their responsibility to ensure that toxic material on the site is properly treated. That does not appear to have happened so far.

In reality, the Environment Agency has a much greater role to play in resolving the contamination issue than the Committee has assigned it. It is an issue that the Secretary of State would do well to address. The examination of riverbed sediment and the control of maintenance dredging alone are not the answer.

We are grateful to Simon Gibbon of Climate Action Stokesley and Villages for technical assistance in the preparation of this report

This report was amended on 14 November 2022 to indicate that PD Ports officially confirmed that they continue to clean up contaminated discharge from the Lackenby Outfall.