Joining the Dots:

The Tees Freeport

and the

Mass Destruction

of Sea Life

Scott Hunter

6 December 2023

In recent months, the national press has finally woken up to the dubious goings on at the South Tees Development Corporation, subsidiary of the Tees Valley Combined Authority. Goings on that have led to allegations of corruption, and a notionally independent panel being set up to investigate them.

The issue of the extent to which the panel’s investigation is being stage managed by Secretary of State for DLUHC, Michael Gove, has attracted a lot of attention. Little or no attention, on the other hand, has been given to the wider issues around the way in which the Teesworks site is being redeveloped –with indifference both to environmental harms and health and safety at work, where the project continues to be shielded from scrutiny by a range of government agencies.

Recent press attention has focused on the corruption allegations, without connecting it with those other issues. Many people in the region are convinced that the mass crustacean die-off in late 2021 was due to work on the Teesworks site. But how are the two things connected? Time to join the dots and get the full picture.

National Press Reporting on Teesworks Issues

When the investigation was announced, Oliver Gill, the Daily Telegraph’s chief business editor, reported on the fact that, in addition to the issue of corruption by the mayor, there was the matter of the STDC site being awarded freeport status (Daily Telegraph, 21 May 2023). In that article, he correctly pointed out that, given the enormity of the task of remediation on the site, having the land in a fit state to welcome new industry within the government’s time frame was a very tall order.

During 2022, meanwhile, numerous reports appeared in the press regarding mass marine mortality around the North East coast that had begun, cause officially unknown, in the autumn of 2021.

Within the same time frame, the national press took no interest in reports of health and safety lapses on the site, nor in the reckless abandon with which capital dredging for the South Bank Quay was being undertaken. Defra’s partner agencies showed no interest either.

Teesworks, an unlikely candidate for freeport status

In brief, the development of freeports, managed by the Business Department (BEIS), is the government’s silver bullet to create post-Brexit economic growth and prosperity. Who can forget when all the talk was of ‘buccaneering free trade’ and ‘global Britain’?

The Government wants a quick return on this in order to be able to claim it as a positive outcome of Brexit. In 2021 it announces eight freeports, seven in areas where such a development is relatively straightforward, plus Teesside, where it is not. The project demands the redevelopment of available land parcels to create ‘tax zones’. The trouble is that the main land parcel on Teesside is heavily contaminated, and proper remediation will take years (and millions). There is no denying that the region urgently needs investment in regeneration, but it is out on a limb compared to the other freeports.

Conservatives win lots of seats in the North East in the 2019 election, having previously experienced the surprise election of a Conservative, Ben Houchen, as Tees Valley mayor in 2017. When the policy of ‘levelling up’ is developed after the 2019 election, the Tees Valley becomes its epicentre, making Houchen an influential figure in buccaneering circles. The freeport, announced by then Chancellor Rishi Sunak, in March 2021, follows from that, but the project has to work to a tight schedule. Houchen promises to deliver, and government money flows into the region both in the form of grants and also in debt funding.

The mayor announces that redevelopment will be accelerated, and claims that, in order to achieve this, 90% of the shares in STDC have been given to two developers, the STDC’s erstwhile joint venture partners. The deal is, essentially, that the STDC puts up public money to pay for land remediation and decontamination, while the developers exploit the site’s potential to generate revenue, whether through leasing land parcels or extracting value from resources on site.

The new schedule involves bringing forward the programme of demolition of derelict structures on the site (demolition is classed as remediation and is paid for by STDC). These begin on 21 September 2021.

A couple of days later, Michael Gove comes to visit the site for the first time, and is well impressed by what he sees there. So impressed, in fact, that he makes a speech about his visit at the Tory Party Conference. In that speech, Ben Houchen emerges as the hero of levelling up, and Teesworks a hive of regeneration activity (as we reported at the time: Are Those Beer Goggles You’re Wearing, Mr Gove?)

Between the visit and the speech, however, catastrophe begins to unfold at Teesmouth.

Mass Mortality Event begins at Teesmouth and Spreads Southwards

In early October, shellfish start washing up on beaches around Tees Bay in vast numbers, and shortly after the die-off continues southwards down the coast almost as far as Scarborough. The Environment Agency (EA), with the help of the Centre for the Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) sets out to investigate what might be causing this. The only abnormality they uncover is high levels of the solvent pyridine in crab tissue, and therefore that the die-off must be the result of a pollution incident.

The problem with this is that the most obvious source of that pyridine is Teesworks, the STDC site, where there are known to be deposits of coal tar, of which pyridine is a component. However, the coal tar has been on the site for decades without leaching out and killing sea life. If this turns out to be the source of the contamination, it is highly embarrassing for those involved in the redevelopment of the site, and the government that is both financing and promoting it.

Have the developers been cutting corners in order to stick to the government’s time schedule for the freeport? Ecocide as a by product of Brexit? Not a good look.

At the end of November 2021, responsibility for investigating the event shifts from the EA to Defra. At this point, the collection of samples comes to an abrupt end. All subsequent mortality events, which continue through 2022, are blamed on the weather, and Defra claims publicly that the initial event was down to natural causes – an algal bloom, to be precise.

Privately, Defra commissions research to demonstrate that the EA’s analysis of tissue samples is incorrect (the report that was finally published on 3 November 2023. (That report is here, and our discussion of it here).

The fishers whose livelihoods have been severely affected are sceptical of Defra’s official explanation and commission their own research (undertaken by a consortium of universities and led by Dr Gary Caldwell of Newcast;e University). Meanwhile, Defra closes its investigation and publishes a final report which definitely and finally rules out pyridine contamination as the cause.

The research commissioned by the fishers contradicts this denial, and it shows the (previously unknown) levels at which pyridine becomes toxic to crab and lobster. When Defra is forced (by the Parliamentary EFRA Committee) to set up an independent panel to evaluate the evidence, it sets the terms of reference in such a way that the panel will examinewhat the cause of death may have been, but not where any contamination may have originated.

This is both dubious and curious. Dubious because it directs attention away from Teesworks as the possible source; curious because it turns out that the EA had already undertaken some investigation on the Teesworks site in 2021 and found no pyridine there. So did Teesworks already have a clean bill of health?

Environment Agency investigates Teesworks in 2021

A report by the EA Coastal and Estuarine Assessment Team, 17 November 2021, contains the following statement:

So, Teesworks is identified as a possible source of pyridine, and both surface water discharge and coal tar are analysed. So far so good. We might also infer from “which is undergoing redevelopment” that the team recognized the redevelopment itself is linked to pyridine discharge.

What comes next, however, shows that the investigation was quickly abandoned:

Despite the fact that surface water outfalls may carry contaminants, and that EA officers were unable to identify any cause other than pyridine contamination, further investigation of surface water outfalls was not carried out because there are too many of them.

At this point, we get an inkling of why Defra may have been reluctant to make this information public. It shows not that Teesworks has been exonerated, but that the EA failed to undertake a thorough investigation in good time. In fact, it was doing little more than go through the motions of an investigation. And Defra went further, by setting out to dismantle their evidence of pyridine contamination in crab and lobster tissue. And then invented another explanation (algal bloom), and then another (unknown pathogen). And threw the North East fishing industry under the bus in the process. Because it was expedient. Because it was deemed essential that no spotlight be shone on Teesworks. Culpability denied.

Historical and circumstantial evidence

When the time comes for a proper investigation into Teesworks’ role in the mass mortality event, there is some circumstantial and historical evidence that will need to be taken into consideration. That evidence links the die-off directly with the development of the freeport.

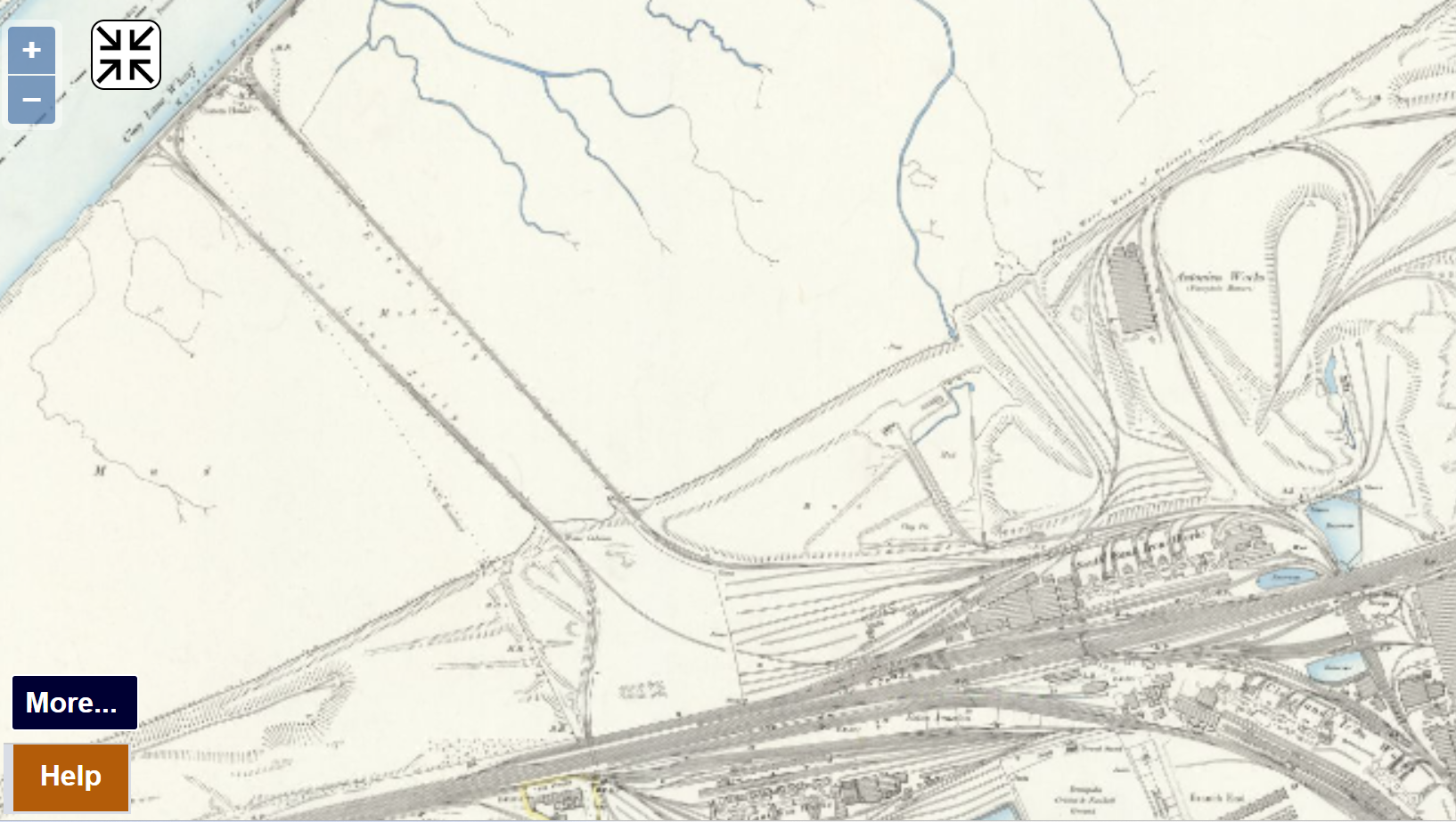

In late summer of 2021 one of the main areas of activity was at the southern end of the site, in preparation for the arrival of contractors, Graham Construction, to build the South Bank Quay. While the EA was concerned about the possibility of surface water carrying contaminants, the contemporary map of that part of the site shows no watercourses. Here is the satellite image of the site as it looks today:

Source: National Library of Scotland, https://maps.nls.uk/view/188154588

There are no watercourses here. However, if we look at historical maps the situation is quite different. Here is the map of the site as it was in 1895:

Source: National Library of Scotland, https://maps.nls.uk/view/188154588

The area is crisscrossed with watercourses, there are also various ponds and at the bank of the river is an area of low-lying mudflats. These watercourses were later covered over as further industry was sited there.

By 1914 they are no longer in evidence, but instead we see a reservoir on one part of the site:

Source: National Library of Scotland, https://maps.nls.uk/view/188154588

In 2017, the first draft of the STDC masterplan for the site describes the South Bank area in the following terms:

“SOUTH BANK Following reclamation from the river during the late 1890’s, the site was occupied by Cleveland Saltworks, Iron and Steel Works, Galvanising Works, Concrete Works, a fuel oil storage depot and more recently South Bank Coke Ovens (SBCO) and Bi-Products facilities. Ground contamination associated with these activities is likely to be locally significant and particularly concentrated at SBCO and Bi-Products facilities. Residual coal-tar is stockpiled to the west of the Bi-Products works. The slag used to reclaim the site is up to 10m thick, and is underlain by compressible soft and weak Tidal flat deposits from the former estuary, and beneath that is the Tees Laminated clay. The bedrock in this area is the Mercia Mudstone at 18-25m depth below ground, and the Boulby Halite formation from which brine was historically extracted.”

Both the 1895 and the 1914 maps, in fact, mark two saltworks in this vicinity, where halite was mined, a fact that the Masterplan doesn’t mention. It also doesn’t make clear that the South Bank area of the site was the oldest (the Redcar works, at the northern end of the Teesworks site were not developed until the late 1970s).

As for the slag used in the reclamation, it is the waste product of iron and steel making. UK iron ore deposits have a low metal content, typically 24 – 30%. The production of pig iron in this country, therefore, generated large quantities of waste material (which reduced after the UK started to use higher quality imported ores in the 1960s). This is what much of the ground on the Teesworks site consists of, as the Masterplan states, to a depth of 10 metres in places, creating a flat, serviceable landscape, into which contaminants were liberally poured for over a century.

Then, on 21 September 2021, three buildings, all in close proximity, were demolished:

Gibbon-Wilputte battery waste gas chimney (95 metres tall)

Gibbon Wilputte coal bunker (68 metres tall) (2,000 ton capacity)

Dorman Long coal bunker (5,000 ton capacity) (56 metres tall)

The demolition required 450kg of explosive. (That’s quite a lot, by the way. The Redcar Blast Furnace, by comparison, was brought down with 175kg, according to the Teesworks website).

At this point, we must start to ask the questions that Defra and its partners agencies have studiously avoided. What kind of earth tremor would ensue from the detonation of 450kg of explosive? How much more severe would the impact be when the site is made of a fragile (by geological standards) layer of slag resting on a layer of soft mud and Mercia mudstone (and whose structure is further compromised by historical mining activity)? Where that ground is known to hold significant quantities of contaminated material, what is the risk that the detonation triggers leaching of those contaminants into surrounding water?

In email exchanges with the Environment Agency, we have sought to uncover whether they had demanded that a relevant Environmental Impact Report be carried out. They have been a little shy in their responses, but the answer, ultimately, is that they did not. It was left to the STDC and the demolition contractors to make such risk assessment as they saw fit (and we didn’t ask the STDC/TVCA. They refuse to correspond with us, and they are notoriously uncooperative when presented with freedom of information requests).

The EA states, in the 17 November report, that it tested samples of coal tar from the site. The STDC states that residual coal tar is stored on site. The EA claims that it found no pyridine in the coal tar it sampled. We have now written to them to ask where they obtained the sample from. Pyridine is a solvent. It will (eventually) evaporate from coal tar stored above ground. Did they excavate the site and take some from below the surface (where the pyridine content of the coal tar is more likely to be preserved)? We’re waiting to hear from them.

Environment Agency’s Half-hearted Investigation

As it undertook no risk assessment of the proposed detonation, the EA was then in no position to gauge how much leaching of contaminated material there was. Analysis of samples of residual coal tar stored above ground was pointless, if that is, indeed, what they did. And in yet another way, the EA’s investigation of the Teesworks site was less than half-hearted, despite being infinitely better than what succeeded it.

Their 17 November statement reports that they could not investigate outfalls along the length of the river as they are too numerous. In fact, one powerpoint presentation we have obtained shows that they sampled water quality at two locations along the river – one near the Seaton Channel and one to the south of Tees Dock.

It is difficult to tell conclusively from the indistinct map (in which ‘WQ’ stands for ‘water quality’), but it looks as though location 16 may be the Lackenby Outfall. This location is notorious, and Tees Valley Monitor has already devoted an entire article (Poison Earth: How Teesworks Exports its Toxic Legacy) to investigating why sediment contamination there is so much greater than at any other site on the river/estuary. Not to have sampled here would have been nothing short of negligence, and background contamination levels here had been recorded in an environmental Impact Assessment carried out in preparation for the South Bank Quay in 2020. (But, given that they appear to have had no idea where the contamination came from, it is surprising that they did not also sample at Dabholm Gut, the watercourse that carries industrial effluent from facilities at Wilton as well as some from the Northumbrian Water Effluent Treatment Plant).

Leachate from the Lackenby Channel is usually the most prominent source of contamination in the Tees, but given the mass of culverts across the whole site, it may not have been the main export route in this instance.

Having failed to find the pyridine source, officers at EA then cast doubt on the idea that it was, in fact, a pollution incident on account of its longevity. They considered that chemical discharge would have become quickly diluted (and raw pyridine is water soluble) and so would not have continued to kill off shellfish for the next two months.

This appears reasonable but fails to take two things into account. The first is that the die-off did not last for two months. It continued throughout 2022, with repeated unusual wash up on beaches, all of which Defra dismissed as due to weather events; and frequent reports from fishers that they were finding large numbers of crab and lobster already dead in their pots, and also from merchants who reported that shellfish were dying in their tanks in unprecedented numbers shortly after arrival.

This the EA didn’t bother to attempt to explain at all. And the Food Standards Agency, meanwhile, couldn’t make its mind up as to whether shellfish caught in North East waters remained safe to eat, so just avoided saying anything about it at all (as is reported in the tranche of documents we have obtained).

The Role of Dredging

So, how could a contaminant continue to destroy sea life over such a prolonged period of time and not quickly disperse in the water? This has to be to do with its adsorption to sediment.

At the end of September 2021, fishers noticed a large, unknown dredger (the Orca), working on an area at Teesmouth. It completed its work just a couple of days before the first die-off was reported. Quickly rumour spread that this must be the cause of the die-off. That dredge was commissioned by the Harbour Authority, PD Tees, who then went to great lengths to explain to fishers, the public, and us at Tees Valley Monitor, that it was only carrying out a routine maintenance operation, and not recklessly ploughing the depths.

We accept that explanation, but there remains the matter of whether the Orca dredge inadvertently contributed to the spread of contaminants further afield.

Part of that explanation concerned the nature of the area being dredged, which is a sand bar that requires more frequent dredging than any other part of the estuary. Tees Bay is a turbulent water body that drags in large quantities of sand to this location. The sand is free of contamination (relatively) when it arrives, but not when it is dredged and removed.

This sand is deposited at a drop zone several miles offshore, known as Tees Bay A. Contamination levels at all dredge deposit sites around the coast are monitored annually by Cefas (under a contract known as SLAB5). Tees Bay A has always been more contaminated than any other dredging disposal site in UK waters. So, contamination travels continuously downstream from the estuary to Teesmouth, where it adsorbs to the incoming fresh sand.

PD Tees maintains the channel for shipping, and the material it removes, while contaminated, has never previously induced a mass mortality event. However, the volume of contaminated material that may have been triggered by the demolition would have altered the composition of the dredge spoils meaning that what was deposited at the drop zone was much more toxic than normal. And no testing of that drop zone was undertaken in the period when the die-off was being actively investigated. Another opportunity missed (or perhaps, studiously avoided).

Crustaceans and North East Fishers, Victims of Charlatan Economics

The blow down of the Dorman Long Tower made all the papers and the news bulletins. Causing explosions creates a spectacle and attracts the media. A perfect way for a publicity-hungry mayor to demonstrate to the world that Teesworks meant business, and the freeport was on its way.

A campaign had been launched to save the tower, on account of its architectural merit, and also because it would stand as a monument to the region’s industrial past. Houchen turned this into an argument of heritage vs jobs. The tower was deemed to be standing in the way of progress.

Who Runs Teesworks?

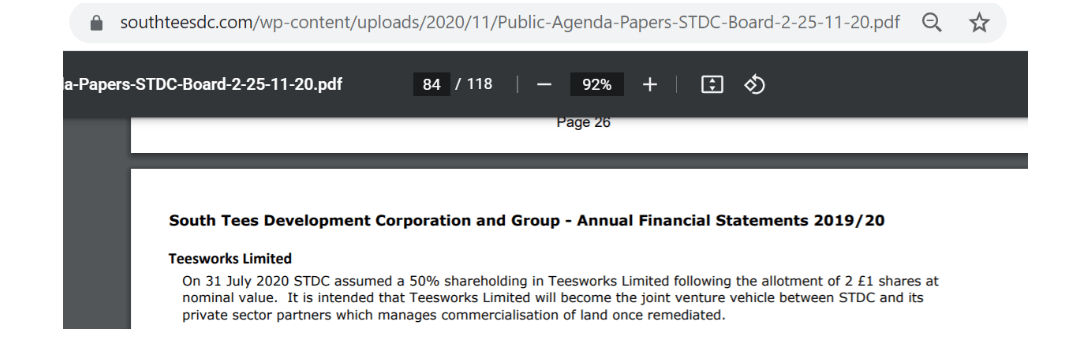

The management of that ‘progress’ is technically in the hands of the joint venture company, Teesworks Ltd, formerly STEL, as shown here in a STDC board document from 2020:

Undoubtedly, this commercialisation will eventually happen, at least in some degree, but it is worth pointing out that, despite the zeal with which all structures on the site have now been demolished, three of the site’s four sites named clients – Net Zero Teesside, TV ERF (the Grangetown incinerator), and Circular Fuels, are infrastructure projects and have no connection with the import/storage/remanufacture/export that is the main (lawful) function of any freeport. And the tower itself was demolished notionally to make way for the GE Renewables factory, a project that was later abandoned.

Thus, in terms of the redevelopment of the site, its destruction achieved nothing. The demolition was a PR exercise.

To have admitted that the redevelopment work on ths site might have been responsible for the contamination of the estuary and beyond would have caused reputational damage to the freeport project. Accepting responsibility is not in the spirit of buccaneering. Thus it fell to Defra to be the defenders of the enterprise.

Government Agencies look away

So, Defra and its partner agencies, effectively or deliberately, turned a blind eye to activity on the Teesworks site, just as BEIS turned a blind eye when Houchen gave away 90% of its shares to Corney and Musgrave. When DLUHC presented the White Paper on Levelling Up in early 2022, it presented Teesside and Teesworks as a fait accompli. Everything turned into make believe to sell the idea of the success of the freeport project.

In reality, the freeport was an idea born out of desperation. Brexit had been sold to the public as a vehicle for creating a bright economic future by Brexiters who actually had no idea how that might be achieved. In 2017, the idea of transforming Britain into a brash Singapore on the edge of Europe chimed with the spirit of the age. The occasional act of vandalism notwithstanding.

Teesworks’ Achievement

The irony of this is that the destruction both of the tower and the sea life ahieved nothing in terms of regeneration. Houchen had presented the GE Renewables Factory to the public as a done deal, knowing that, in reality, no lease agreement had been signed. There is so much contaminated material to such depth on the site that it is not being fully remediated, but simply having the surface removed and the ground capped to prevent further leaching of contaminants. All in the service of a fantasy of economic regeneration.

Much has been written recently to show generally how lacklustre the freeport project is. But even at its most promising, it is a quick fix, not a planned long-term commitment to invest government money in regional economies. But no quick fix will suffice on Teesside. Some creativity is needed to do that, but the current administration is creative only with the PR that attempts to keep the local electorate happy (and misinformed).

Were the regeneration of the site to be done more thoughtfully, it may allow that the contaminated material that is present in such abundance, is actually potentially an exploitable resource. Slag contains a considerable amount of recoverable material, from metals to rare earth elements (“Legacy iron and steel wastes in the UK: Extent, resource potential, and management futures”, Riley et al., 2020, Journal of Geochemical Exploration, vol 219). Teesworks, on account of its size and the volume of material concentrated on site, may be well suited to such an initiative. However, to make that into a reality requires both vision and commitment. Not qualities characteristic of the average buccaneer.

When proper investigation into Teesworks and the TVCA finally takes place, it must take into account not just the issues of financial impropriety that are the subject of the current investigation, but also culpability for the environmental and economic damage it has caused. The current investigation, quite regardless of its lack of independence, only scratches the surface of the the issues involved here.